Many aspects of the founding of the William Marsh Rice Institute in 1912 inspired wonder, respect and optimism. Its visionary young president, Edgar Odell Lovett, courted scholars from around the world in order to open a university “of the highest grade.” Its charter invited women, alongside men, to engage in rigorous academic study, and its Mediterranean-influenced architecture countered Houston’s dull and swampy plains. Born “in the joy of high adventure, in the hope of high achievement, in the faith of high endeavor,” as Lovett said in the opening ceremony, Rice’s beginning was audacious indeed.

And yet in one profound way, Rice ran with the crowd of Southern universities of its day. The Institute was expressly chartered to educate “the white inhabitants of the City of Houston and the State of Texas.” And for its first 50 years, Rice remained segregated.

The road to integration at Rice meandered in ways that were both peculiar to the institute and typical of its Southern home. For example, in 1948, when Rice Thresher editor Brady Tyson expressed support for integration, Rice President William V. Houston dismissed the conversation as “entirely academic.” For years, the legal force field that was the original charter suppressed both public debate and action.

Under President Kenneth Pitzer, in 1963, the Board of Governors began legal proceedings to change the charter, allowing Rice to begin charging tuition and to integrate. Just when it looked like the legal barriers to integration would fall for good, alumni intervened in Rice’s own legal action and tried to prevent it. Finally, in 1965, two African-American students joined the student body. (Raymond Johnson ’69, a doctoral student, had enrolled the year before.) The next year, two more African-American students enrolled. While Rice’s legal desegregation was history, the development of a supportive community was still a dream.

Illustration by Thandiwe Tshabalala

The following timeline and oral histories explore the steps that led up to Rice’s desegregation and feature the voices of black alumni who lived that experience. This past year, the Association of Rice University Black Alumni (ARUBA), together with other Rice offices, organized a series of thoughtful forums and joyful gatherings to mark 50 years of black life at Rice.

But the celebration was not only about looking back at how far Rice has come in 50 years. On a recent Saturday morning during ARUBA’s gala weekend, a panel of Rice administrators, staff, faculty, alumni and students gathered to discuss the state of black life today. In front of an attentive audience, the panel answered questions on race as a dimension of admissions, of campus social and academic life and, especially, of life beyond the hedges. It was an informative and candid dialogue that signified progress while challenging all of us to create a campus environment that is empathetic, respectful and inclusive. Programs like these inspire us to reach for, in Lovett’s long-ago words, “the hope of high achievement,” today and for the next 50 years. — Lynn Gosnell

“I was just so proud in that moment.”

Check out an eight-minute video that explores the state of black life on campus today. The video was produced by Rice’s Office of Development and Alumni Relations along with the Association of Rice University Black Alumni.

[tw-divider][/tw-divider]

BUILDING RICE

1891

1891

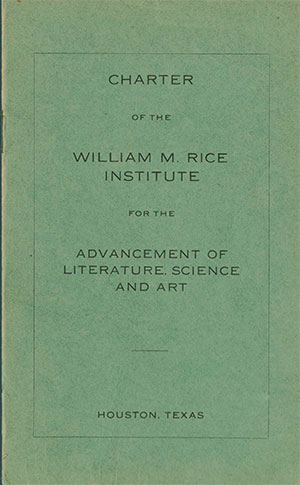

William Marsh Rice (March 14, 1816–Sept. 23, 1900) establishes an endowment for the “William M. Rice Institute for the Advancement of Literature, Science and Art” to be used for “the instruction and improvements of the white inhabitants of the City of Houston, and State of Texas.” The charter also specifies that the institute will have no religious affiliation and will not charge tuition. Captain James A. Baker (Jan. 10, 1857–Aug. 2, 1941) leads the Board of Governors.

1900

On Sept. 23, Rice is murdered by his valet, Charlie Jones, in a plan devised by Rice’s lawyer, Albert Patrick. (Jones turns state’s witness, and Patrick serves time in prison, but is released in 1912.) The Rice Institute’s trustees begin legal work to establish the long-planned institute.

1912

The Rice Institute opens Oct. 12, with Edgar Odell Lovett, a mathematician and astronomer recruited from Princeton, as its first president. By laying the groundwork for a university “of the highest grade,” Lovett vastly expands Rice’s educational mission, which originally proposed the “establishment and maintenance of a Free Library, Reading Room, and Institute for the advancement of Science and Art,” as well as a polytechnic school “for males and females, designed to give instructions on the application of Science and Art to the useful occupation of life.” The first class comprises 59 students.

1917

An Army ROTC is established on campus and students begin various training exercises in preparation for war.

1920s

Enrollment reaches more than 1,000 students. While the Rice Institute is off to an impressive start, financial constraints begin to slow its growth.