After years of teaching students — and colleagues — Dennis Huston is bowing out. Terrence Doody celebrates the way Huston’s singular (loud) voice exemplified the best of Rice.

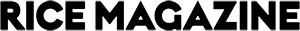

Dennis Huston commands the classroom stage during a spring semester course. Photo by Tommy LaVergne

The day I came to Rice to interview for a job teaching literature, in December 1969, a group of senior English majors took me to Sammy’s and promised to “tell me the truth.” They said I would like Dennis Huston a lot. True.

The following August, when I was visiting my parents in Wheaton, Ill., I heard a couple of guys talking about Yale, took a chance, and asked them of they had ever heard of a Dennis Huston, who had taught English there. “Oh, yeah, man. Great teacher.” True, too.

Later that month, when I pulled into a campus parking lot for the first time, there by chance were Dennis and his family, who adopted me and my family, too. Right away, Dennis became my teaching teacher.

We discussed designing a syllabus. How to define writing assignments and how to pace them throughout the semester. The utility of exams. Grading standards for a student body with high achievements and high standards for themselves — students, in other words, who’d never gotten a B before. Policies for late papers and extensions. How much to write in the margins, and the point at which too many suggestions become demoralizing. Which kind of papers can be improved by rewriting, and which cannot. The immeasurable advantage of discussing a paper face-to-face (“Can you read my handwriting?”). And, maybe most importantly, how to get these very smart people to talk in class.

Some lessons, however, came inadvertently. In spring 1971, Dennis and I were in a Baker Shakespeare production of “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” He was cast as Bottom the Weaver, who believes in the power of the theater as avidly as any character in Shakespeare does and is, therefore, one of Shakespeare’s greatest advocates.

Perfect casting. In the two weeks before opening night, rehearsals ran very late — sometimes until 1:30 or 2 a.m. One morning, after neither one of us had had time to prepare for our 9 a.m. class, I was at his office when he said, “It’ll be OK. I taught it last year and have notes.”

His notes amounted to three words on an index card. I am sure he upped the volume that morning and the class worked, but I promised myself that the first time I taught anything new from then on, I’d write a lecture so complete that I wouldn’t have to worry.

You can’t always be as smart as you want to be, but you can be prepared. What can’t be learned, however, even from a teacher like Dennis, is the depth and quality of his generosity. All good teachers are certain they have something valuable to give others, and what often measures the value of that gift is the joy they take in what they know.

What can’t be learned, however, even from a teacher like Dennis, is the depth and quality of his generosity.

I’ve never known anyone as intense in the classroom as Dennis is. No one fills the room with more compelling energy. And no one on the planet has spent more time grading papers than he has for the whole of his teaching life — because it is important to him that every aspect of every essay by every student, from the commas to the argument’s conceptualization, be as good as possible.

A good five-page paper takes about 10 minutes to read carefully, but it takes much longer to figure out the intention hidden in a not-so-good paper and then to make that intention clear to the writer. This is a Sisyphean task, because all the work it takes to improve the student’s first paper doesn’t guarantee a thing about the second. Still, the more papers the student writes, the better the chances are that the writing will improve. And nothing is as important in anyone’s education as learning to write well.

One of Dennis’ rewards, therefore, has been the chance to write even more letters of recommendation for all of those students who now write better themselves.

He has been known to complain about this a bit. At the same time, he says in every one of these performances that so-and-so is the “most brilliant student I have ever, ever had.” He has a couple of these most brilliant students every year, so by now he must have had well over a hundred of them. The hyperbole is his way of saying out loud how much he loves them and has loved teaching them all.

Teaching is a profession and a vocation. These are neither mutually exclusive nor necessarily antagonistic categories. But there is much more professional reward attached to publishing a paper than there is to grading one. There is also a real but more permeable distinction between saying “I teach literature” and “I teach students.” I’d say Dennis has always taught students first. He has taught them with great fervor and success to read Shakespeare; to judge the movies made from the plays; to read Homer, Chaucer and Milton; and to write better papers. It is then for the students to decide, usually much later, whether the reading or the writing has been more important.

I’d say Dennis has always taught students first.

Dennis has won many, many teaching prizes, including the George R. Brown Superior Teaching Award (four times), the Minnie Stevens Piper Professor of the Year award and the Nicholas Salgo Teaching Prize. In 1989, when Dennis was named Professor of the Year by the Council for the Advancement and Support of Education and the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, there was a faculty reception for him in the RMC. “A rising tide lifts all boats,” I thought, and felt that every one of us had been elevated ourselves that day, because we were now colleagues of the best teacher in America. It was also a very anxious moment, because now we had to get better.

THE BEST (AND WORST) OF THE BARD

Photo by Tommy LaVergne

We asked Dennis Huston for his opinions on the highlights — and lowlights — of Shakespearean drama. Here are the short answers; watch Huston expand on these choices and more.

Favorite comedy: “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Favorite tragedy: “Hamlet”

Least favorite play: “Titus Andronicus” — though a great movie by Julie Taymor

Favorite character: Nick Bottom, from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”

Most misunderstood character: Sir Toby Belch, from “Twelfth Night” (He’s not funny, he’s mean.)

Most misunderstood line: “Wherefore art thou Romeo?” (It means, “Why are you Romeo?” not “Where are you, Romeo?”)

Favorite couple: Beatrice and Benedick, who woo with sarcasm and insults in “Much Ado About Nothing”

Favorite sexual innuendo: “… I’ll fear no other thing/so sore as keeping safe Nerissa’s ring,” from “The Merchant of Venice”

Favorite insult: “poisonous, bunch-backed toad,” from “Richard III”

Best Shakespearean film adaptation: Richard Loncraine’s 1995 “Richard III”

Worst film adaptation: Too many bad ones to name

—Terrence Doody is the Allison Sarofim Distinguished Teaching Professor and a professor of English at Rice, where has taught courses in fiction and narrative theory since 1970.

Dennis Huston, one of Rice’s most beloved teachers, retired in May. He is the Gladys Louise Fox Professor of English at Rice, where he has taught a wide range of courses since 1969, including Shakespeare, film and drama. He received his B.A. at Wesleyan University and earned a master’s and Ph.D. at Yale University. Huston has won numerous George R. Brown teaching prizes, and in 1989 was named the nation’s “Professor of the Year,” an honor which earned him an invitation to the White House. “A course with Dennis is not simply a course that ends at a certain time,” said Nicolas Shumway, dean of humanities at Rice. “It is the beginning of a dialogue that lasts a lifetime.” An accomplished thespian, Huston has acted in many Rice productions of Shakespearean and modern plays. In addition, as a guest lecturer, Huston has taught outside the hedges at Rice alumni gatherings across the country, at the Glasscock School of Continuing Studies and for the Teaching Company. Huston has written and edited numerous publications, including “Shakespeare’s Comedies of Play” (1981) and “Classics of the Renaissance Theater: Seven English Plays” (1969). He has been active in campus life and served as master of Hanszen College — twice (1978–1982 and 1992–1998). Huston has two children and two stepchildren. He is married to Lisa Bryan Huston. See a video about Huston’s teaching legacy.