Gifted and Black: Push for Integration

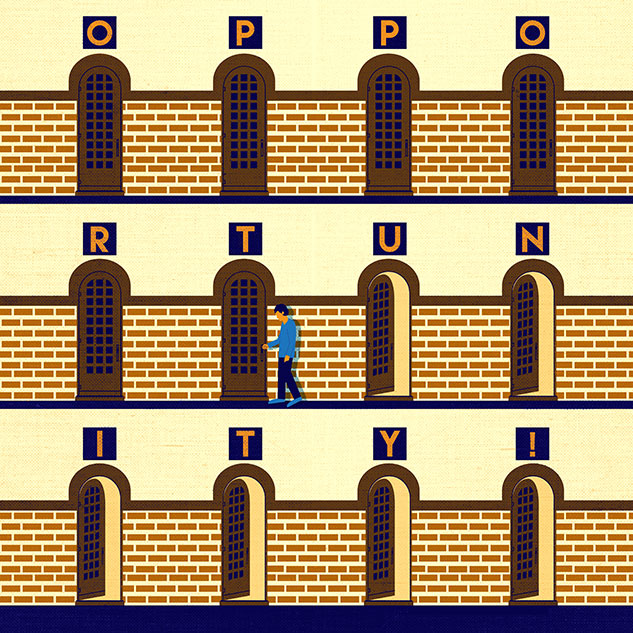

Illustration by Thandiwe Thsabalala

1960

In order to bring Rice’s name in line with its identity as a broader educational institution, the Rice Institute changes its name to Rice University.

1960

President Houston suffers a heart attack and steps down in September. Under the leadership of trustee and alumnus George R. Brown (whose engineering and construction firm Brown & Root was built on federal contracts), a search for a new president begins.

1961

The presidency is offered to Caltech chemist Kenneth S. Pitzer, who says he will not accept the job unless Rice moves to integrate its campus. Pitzer’s own research contract with the Atomic Energy Commission includes nondiscrimination clauses. Pitzer and the board will need to “improve Rice’s stature as a graduate institution” in order to grow Rice into a first-rate institution.

1961

In November, the Student Senate passes a referendum calling for desegregation.

1962

On Sept. 26, Rice’s Board of Governors unanimously passes a resolution to charge tuition and desegregate. Before going public, they inform alumni and other constituents. It takes the school’s attorneys months to file the petition. During that same board meeting, Rice also passes a resolution allowing a fledgling aeronautics agency, NASA, to build its space center on Rice-owned property in Clear Lake.

1962

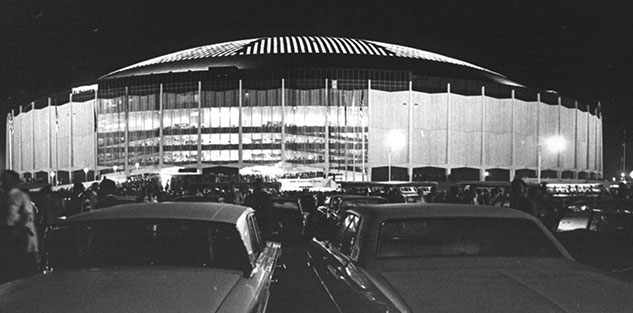

Former Houston mayor Judge Roy Hofheinz secures critically needed support for funding the Astrodome by promising that the facility will be fully integrated when it opens in 1965. “It played a key role in the desegregation of public facilities in Houston,” said Stephen Fox, Rice’s architectural historian, in a 1999 New York Times article about the Astros’ last game there.

WikiMedia Commons

1962

A PIONEERING STEP

Raymond Johnson ’69, a University of Texas graduate, becomes the first African-American graduate student at Rice. Hired as a research assistant in 1963, he had to wait for the admissions policy to be settled before he could officially enroll as a doctoral student in mathematics. While Rice provides a welcoming environment, for the most part, most of Houston is still segregated, and Johnson participates in sit-ins at local restaurants. Johnson will go on to a distinguished career as a math professor at the University of Maryland, where he’ll mentor many African-American students pursuing doctorates in math.

In a 2004 profile in Sallyport, Johnson said, “Racism may be a Hydra, but even the Hydra was killed. Whether you are black, white, Asian, Puerto Rican or Hindu, take on racism where you see it. Take on these problems one at a time. Open the doors one at a time. I know it is hard. I’ve been there.” In a full-circle turn of events, Johnson returned to Rice to teach math in 2009. In 2015, he was one of 14 recipients of the Presidential Award for Excellence in Science, Mathematics and Engineering Mentoring.

Watch a video of Raymond Johnson talking about growing up in Alice, Texas; attending the University of Texas at Austin; and coming to Rice for doctoral studies in math in the summer of 1963 — the first African-American graduate student at Rice. This excerpt is part of “Young, Gifted and Black: Reflections from Black Alumni at Rice,” a 2012 video production by Mouthwatering Media and Rice University.

Raymond Johnson

1963

On April 20, Texas’ attorney general accepts Rice’s argument that “institutionalized racial discrimination” and the inability to charge tuition make it impossible for the board to advance the university’s mission of creating an educational institution of the highest quality. But on Sept. 20, 1963, several alumni file a petition to intervene.

1963

Under threat of some very public civil rights demonstrations (for example, during a nationally televised parade to honor Mercury astronaut Gordon Cooper), Houston quietly integrates movie theaters, stores and restaurants, a culminating step in the civil desegregation process that began with sit-ins and negotiations years before.

1963

An ongoing local media “blackout” of the fight for desegregation draws scorn from state and national press, but the process is peaceful. Black and white college students, businessmen, church leaders and community leaders participate in the effort.

©Houston Chronicle. Used with permission

1964

The new case between Rice and the intervening alumni finally comes to a jury trial in a Texas state district court. In February, “the jury unanimously agreed that William Marsh Rice had intended to create an outstanding university through his gift, and that maintaining segregation would make it impossible to carry out this intent,” Kean writes. This decision allows Rice to officially desegregate, but the legal battle will not be over until 1967.

1964

The federal Civil Rights Act of 1964 overturns all state and local laws on segregation.

1965

In the March 18 issue of the Rice Thresher, staff writer Bill Broyles ’66 reports that Rice is planning to begin charging tuition and to integrate the campus the following fall. An editorial maligns the administration’s decision “to bar public discussion of integration and other subjects related to the race problem, questionable under any circumstance” and “particularly indefensible now.”

1965

In September, two black undergraduates enroll at Rice: Jacqueline McCauley and Charles Freeman III.

1965

At 26 years old, Kennard W. Reed Jr. joins Rice’s faculty as a visiting assistant professor of mathematics. Reed, who is black, comes to the university in 1965, but leaves in 1966 after facing harassment. A native Houstonian, Reed graduated from Fisk University in 1958. He earned both his M.S. and Ph.D. from New York University.

1965

Velma McAfee Williams enrolled in the Rice doctoral program in mathematics, blazing a trail for African-American women at Rice. She left Rice in 1968 and spent her career as an educator and leader who inspired young students to pursue mathematics. In 2016, Rice recognized Williams during commencement ceremonies with honorary doctoral regalia.

1966

In October, the First Court of Civil Appeals affirms Judge William M. Holland’s 1964 ruling that Rice trustees could amend the charter to admit applicants of all races and to charge tuition. In 1967, the Texas Supreme Court dismisses a challenge to this appeal, and Rice’s prolonged fight to change the original charter is over.

1966

Theodore “Ted” Henderson is the first black male undergraduate to enroll and graduate from Rice. Henderson was born and raised in Galveston. Linda Faye Williams, raised in Lovelady, Texas, is the first black female to enroll and graduate from Rice. Both graduate in 1970.