Gifted & Black: Setting the Stage For Change

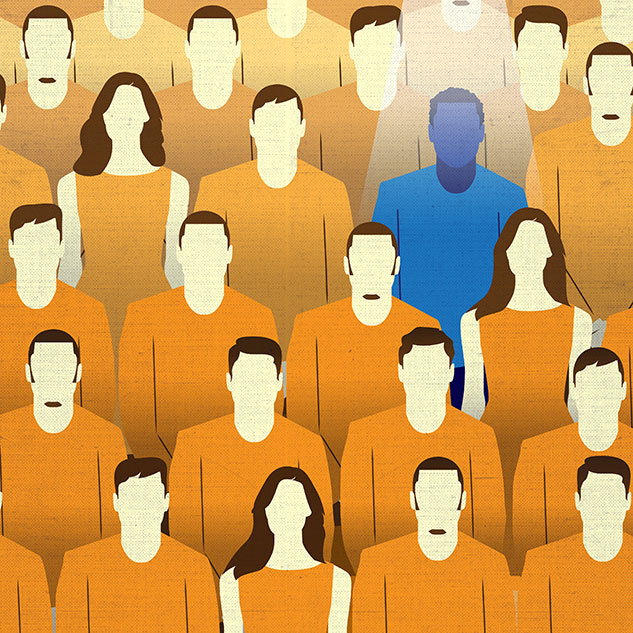

Illustration by Thandiwe Tshabalala

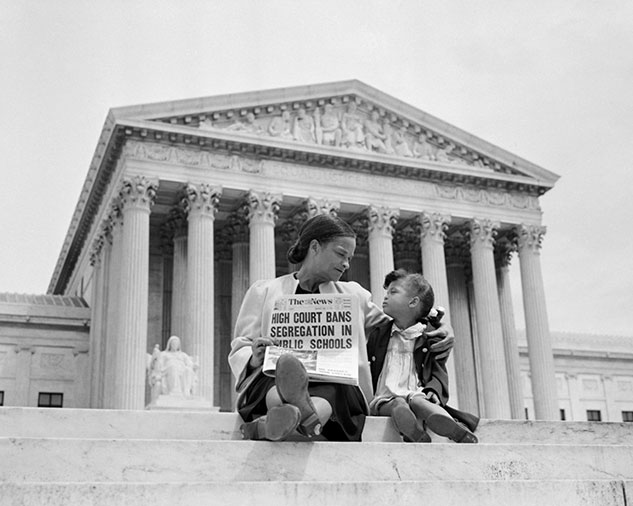

Photo by John Trost

1940s

During the 1940s, Rice begins an expansion built on its science and engineering prowess, nurtured by federal grants in the post-World War II era. The institute’s financial footing is further stabilized by an inheritance from Rice’s nephew (William M. Rice Jr.) and through the discovery of oil and natural gas deposits on its Louisiana properties. But the most important financial windfall for Rice during this time is the purchase of a stake in the Rincon oil field in South Texas. These income streams, say historian Melissa Kean ’00, encouraged “a false sense of financial well-being and a certain detachment from the currents that shifted around it in the late 1940s and 1950s.”

1946

William V. Houston, an eminent physicist, becomes the second president of the Rice Institute. His charge is to implement an ambitious strategic plan to grow the university. At a time when many other universities are racing to capture postwar federal funding, Rice opts not to diversify its finances through government contracts.

1948

Students begin to kick-start a debate via the Rice Thresher. On Dec. 1, editor Brady Tyson reprints editorials from the Houston Post and the Houston Informer, both calling for better race relations. President Houston writes a letter to the editor stating that the Rice Institute was “founded and chartered specifically for white students.”

1950

In response to the pro-segregationists’ cross burning at the University of Texas Law School, Rice Thresher assistant editor William P. Hobby Jr. writes in an Oct. 27 editorial, “The question of admitting Negroes to Rice was fought out in these columns several years ago. The result of that fight was a temporary victory for those who would maintain segregation. That the victory was temporary is a certain fact made temporary by the trend of judicial and public opinion which has in the past few years so diminished racial hatred and prejudice.”

1953

A Rice Thresher student poll on integration shows that 51.6 percent of students support admitting black students, while 39.4 percent oppose integration.

1954

In May, the U.S. Supreme Court strikes down state-mandated public school segregation via Brown v. Board of Education.

Courtesy of Library of Congress

1954

THE CORNELL INCIDENT

In an October 1954 editorial, the Thresher relates an incident that caused significant frustration to its staff. The Cornell University student paper had written to the Thresher to ask for help in seeking sleeping and eating accommodations for a black student on its football team. “Unfortunately, we had to reply that regardless of our personal feelings and regardless of the United States Constitution and the Bible, the State of Texas maintains that this athlete is inferior (incidentally, the inanity of this contention was adequately demonstrated on the playing field Saturday night) and not entitled to equality with his white teammates. Thus again we must hang our head in shame and say only that perhaps the day will not be far off when Rice and the State of Texas will welcome all men equally. Only then will we be able to be proud that we are part of the Rice Institute, and part of Texas.”

1950s

Throughout the 1950s, pressure grows from federal funding agencies to comply with nondiscrimination clauses in grants. “Indeed, the need for federal funding had slowly become Rice’s Achilles’ heel. … Resting on this cushion of oil money, Rice did not pursue grants and contracts with anything like the zeal exhibited by Duke, Emory, Tulane and Vanderbilt. By the mid-1950s, however, it had become obvious that the specialized technical research that was the institute’s strength required equipment so expensive that it could only come from the federal government,” Kean says.