From the panhandle’s plowed playas to the sinking soil of Houston, Texas faces a vast range of environmental issues. Those challenges have evolved as communities have grown, taxing the land but also spawning major conservation efforts. David Todd ’84, executive director of the Conservation History Association of Texas, who earned a master’s degree in environmental science at Rice, and his co-author, Jonathan Ogren, examine the changing face of Texas environmentalism in “The Texas Landscape Project: Nature and People.” The book takes a visual approach to a complicated issue, using more than 400 maps and graphics to make sense of the big data behind this Texas-sized environmental survey.

What inspired you to look at Texas’ environmental issues in this very visual, atlas-like way?

What inspired you to look at Texas’ environmental issues in this very visual, atlas-like way?

We hope the atlas’ maps will help people connect with the coast, the canyons, the high plains or the deep forests of the state; anywhere that strikes a chord.

Did you come across any surprising finds during your research for the book?

I was struck by how Texans are volunteering far and wide for conservation: tagging birds, sampling streams, planting prairies and reintroducing rare wildlife.

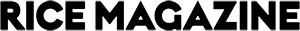

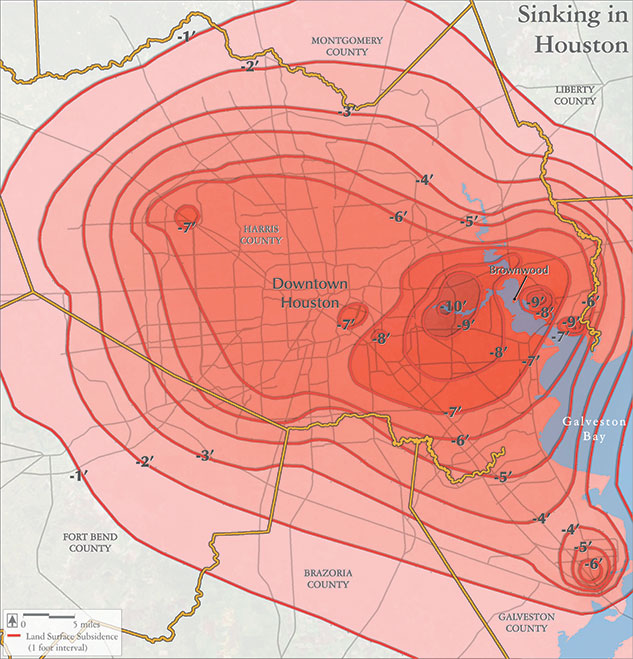

The book includes an alarming graphic of the degree to which Houston is sinking. How worried should Houstonians be about that?

Parts of Houston have sunk by as much as 10 feet due to groundwater use but, fortunately, subsidence has slowed as the city has switched to surface water. Still, the city’s monsoons, flat terrain, tight clay soils and extensive paving will likely continue to bring high water. Keep your rubber boots!

The book includes this chart of Houston’s “land surface subsidence” — or sinking — between 1906 and 2000. Some areas have dropped by as much as 10 feet. Map courtesy of David Todd

You tell the sad story of the Kemp’s ridley sea turtle, a lovable-looking 100-pound Gulf denizen, which began to die off not long after it was discovered. Do efforts to preserve this species have a chance at succeeding?

The Kemp’s ridley sea turtle teaches us that even very rare species can bounce back with smart research, steady work and cooperation. However, the recent stall in the turtle’s 30-year revival (likely due to the 2010 Deepwater Horizon explosion and the resulting oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico) reminds us that we always need to be cautious.

You also write about a less lovable Texas resident, the fire ant. Why should we care about fire ants?

Red imported fire ants are a concern for their damage to endangered species, game birds and a variety of pollinators, lizards, turtles and snakes. Plus, they have brought out the worst in humans, inviting chemical dousings with often counterproductive results. In the end, the ants remind us of how invasive species can bring severe and unpredictable impacts.

You mention that some people have called our era the “Sixth Great Extinction,” likening it to the die-out of the dinosaurs. Is that accurate?

I think it’s fair — and sad. A global sample of 10,000 species found that their populations shrank by an average of more than 50 percent from 1970 to 2010. Current global species losses are estimated at 100 to 1,000 times the prehuman extinction rates.

Is there a region in Texas you think is facing the gravest environmental danger right now? Texas’ native prairies are likely facing the biggest challenge: Many of them have been destroyed by cultivation, overgrazing, grading and paving. For instance, less than a tenth of a percent of the state’s Blackland tallgrass prairie remains. For a state that was once mostly grassland country, this is clearly worrying.

Read more about “The Texas Landscape Project.”