Archivist Norie Guthrie is on a quest to recover and preserve Houston’s role as a folk music hub. Doing that requires a lot of hanging out with the people and places who shaped that past (and present).

Norie Guthrie at Houston’s Anderson Fair. Photo by Tommy LaVergne

When Houston gets its due as a music hub, you hear about its hip-hop, country, zydeco, blues, R&B, jazz, and rock ’n’ roll.

And justifiably so: It’s a city where you once could have heard blues both earthy and down-home (Lightnin’ Hopkins, Juke Boy Bonner) and suave and uptown (Bobby “Blue” Bland and Clarence “Gatemouth” Brown). As the city where Louisiana Creoles melded their Francophone “la la” music with blues and R&B, the Fifth Ward’s Frenchtown neighborhood is credited as the birthplace of zydeco. Some music scholars claim that the 1949 Goree Carter single, “Rock Awhile,” recorded next door to what is now Katz’s Deli on lower Westheimer, was the very first rock ’n’ roll 45 ever waxed. No other band as thoroughly Texan as Houston’s ZZ Top is so prominently enshrined in the canon of classic rock, and Houston helped give rise to psychedelic rock (the 13th Floor Elevators recorded for a local label). There was the Urban Cowboy craze, and it was Houston (not Atlanta) that put Southern hip-hop on the map via the Geto Boys. Of course, Houston launched the phenomenon that is Beyoncé. Not bad for a city most outsiders regard as a distant second fiddle to Austin.

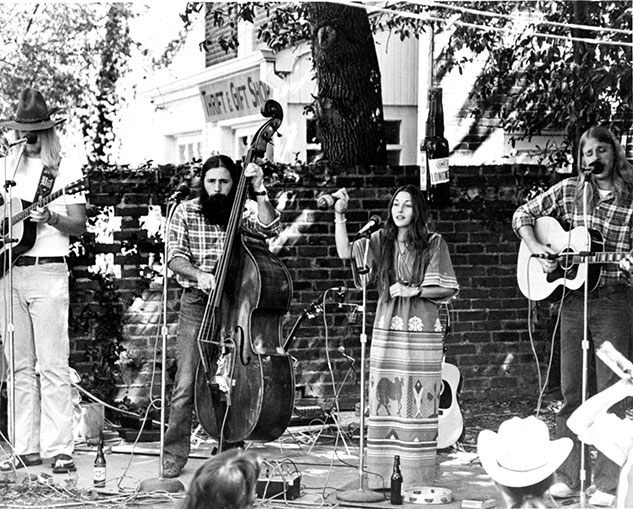

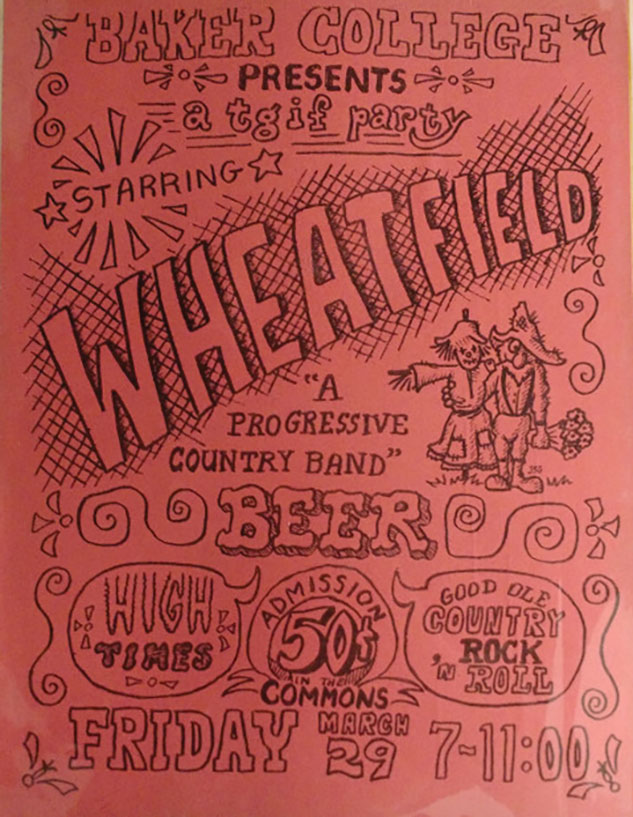

Wheatfield: L to R: Cris “Ezra” Idlet, Bob Russell, Connie Mims and Craig Calvert, ca. 1974.

Wheatfield concert flier at Baker College, March 29, 1974

Amid all that melody, rhyme and rhythm, Houston’s stellar folk music history tends to get lost in the shuffle. All too often, artists who made their names in Houston are, thanks in no small part to numerous appearances on “Austin City Limits,” associated with the state capital.

Nevertheless, it was the Bayou City, and not the Live Music Capital of the World, that served as the earliest muse for latter-day folk, country and Americana legends Townes Van Zandt, Guy Clark, Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, Rodney Crowell, K.T. Oslin, Eric Taylor, Nanci Griffith and Lyle Lovett, among many others — and since 2016, Rice special collections librarian and archivist Norie Guthrie has been assembling a trove of vital artifacts from that often-overlooked music scene.

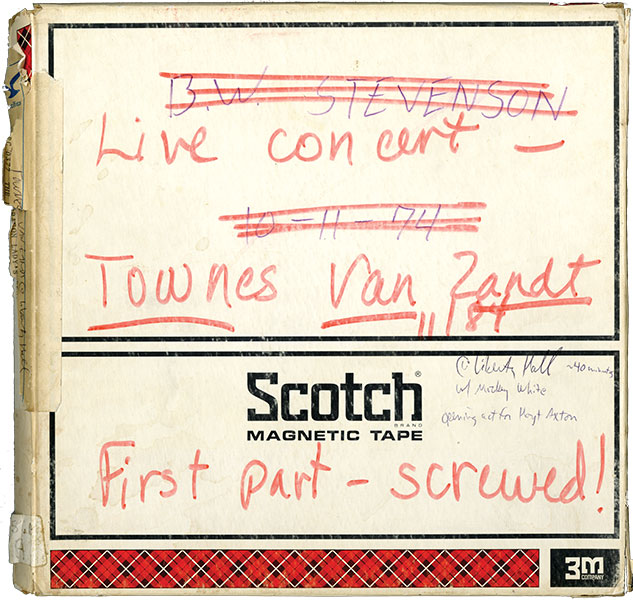

Reel-to-reel of Townes Van Zandt live from Liberty Hall broadcast on KPFT, Nov. 1984

I have had a front-row seat for that scene my entire life. My grandfather, John A. Lomax Jr. (brother of folklorist Alan and son of folklorist John Avery Lomax), helped shape it, from the 1950s until his death in 1974. My parents, the late Julia “Bidy” Taylor and John Lomax III, were friends and contemporaries of Clark, Crowell, Williams and Van Zandt, and my dad worked as manager for Van Zandt and Steve Earle. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, my aunts were huge fans of Shake Russell and Dana Cooper, and as music editor for the Houston Press for most of the 2000s, I was privy to the ins and outs of more recent Houston folk.

The fledgling Houston Folk Music Archive is already home to an impressive collection of scrapbooks, correspondence, flyers, posters, films, photographs and hour upon hour of recordings (a great many of them live on-campus concerts broadcast by KTRU). It captures the subculture’s 1960s–1980s heyday, a time of immense creativity, when folk music was every bit as vital to disaffected Bayou City youth as punk would become a generation later.

Margaret “Mimi” Lomax, Joseph Lomax and John Avery Lomax Jr., 1949. John Avery Lomax Jr. founded the Houston Folklore Society with Ed Badeaux, Howie Porper, Chester Bower and Harold Belikoff in June 1951. Courtesy of John Lomax III

Speaking amid boxes of archival materials at a conference table on the first floor of Fondren Library, Guthrie said that the KTRU recordings — often gigs at places like the Baker College Commons, Rice Memorial Center, Hamman Hall and, later, Willy’s Pub — were the impetus for the collection’s founding in January 2016.

“Once we got the reels from KTRU, I realized we had such a great document of these interactions,” Guthrie said. “And in our collection parameters, we collect Houston materials and fine arts. So I went to Lee Pecht [university archivist and director of Special Collections at Fondren Library] and said, ‘We have all these things, why don’t we put them out there and see what happens?’ No one else was doing it. It just made sense.”

With the recordings as the archive’s cornerstones, Guthrie set about laying the foundation.

Her first email went to Craig Calvert, guitarist of the band Wheatfield (later called St. Elmo’s Fire) that almost, but not quite, made it to a major-label recording contract in the 1970s. (Wheatfield was featured on “Austin City Limits” during the program’s first season, and Calvert’s former bandmates Keith Grimwood and Ezra Idlet went on to form the folk/children’s music duo Trout Fishing in America.)

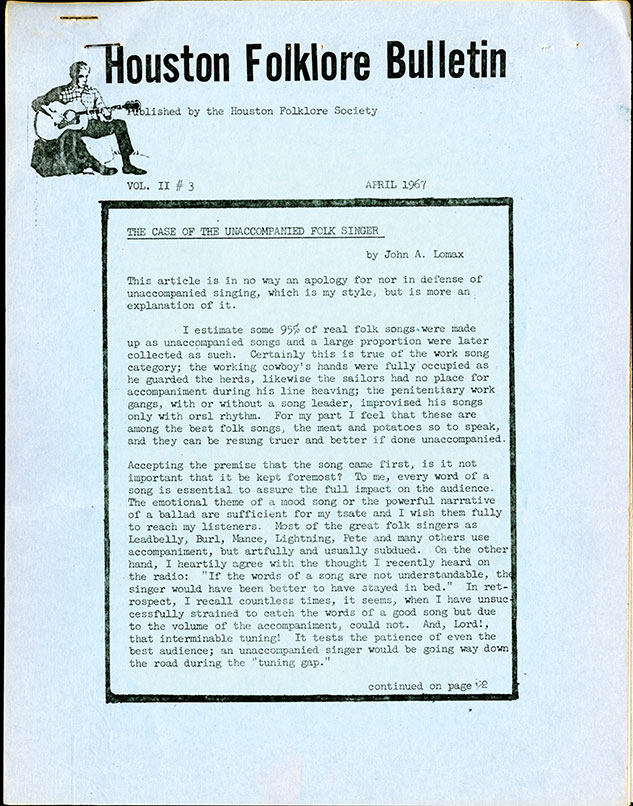

Front page of Houston Folklore Bulletin, April 1967

Word got around the folkie grapevine fast. The day after Guthrie talked to Calvert, another 1970s-era folk mainstay, singer-songwriter Danny Everitt, showed up at Fondren. “Danny said I needed to sell the project,” Guthrie recalled. “I wrote a blurb explaining why we started the Houston Folk Music Archive and our goal. I decided we should collect materials starting with the Great Folk Scare [that brief window in the 1960s when folk music topped the pop charts] and moving on to the 1980s, when Dana Cooper and Lyle Lovett, among others, still used Houston as their home base. Those roughly 20 years were an incredibly fruitful time,” Guthrie said.

Thanks in large part to my grandfather, Houston’s folk scene had something precious few others did: a deep infusion in the real-deal blues. Pops, as he was known to his family, founded the Houston Folklore Society, and in addition to his own bass-baritone a cappella renditions of the Texas folk songs he’d learned from his dad, and the blues he’d learned from Leadbelly, the concerts he hosted in Hermann Park and at the Jewish Community Center also featured people like Third Ward blues star Lightnin’ Hopkins and Navasota blues-folk-country-ragtime guitarist Mance Lipscomb. Future folk superstars like Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark were regular attendees.

“For a 21-year-old folksinger, it was heaven,” Clark told No Depression magazine in 2002. “Both Lightnin’ and Mance were brilliant guitar players, though neither were flashy, and that taught us that it’s not always the notes you play that make a difference; it’s also the holes you leave. We eventually applied that to our songwriting. You don’t want to tell the listener everything; you have to leave room for them to imagine how their grandfather would have said it. It makes them feel smart; it makes you feel smart; and everyone is happy.” Clark’s and Van Zandt’s time as full-time Houston musicians was relatively brief — but utterly vital. Before they followed fellow Houstonian, surrogate father figure and platinum-selling songwriter Mickey Newbury to Nashville, they set a world-class standard for all who would dare follow them on Bayou City stages.

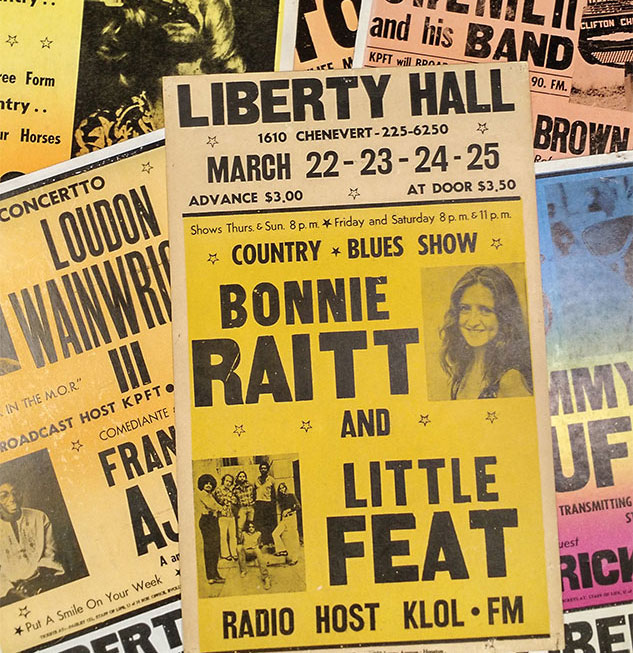

The Rice archive also chronicles the rise and (with one important exception) fall of Houston folk’s key venues: the Jester Lounge, Sand Mountain Coffeehouse, and downtown’s Liberty Hall and the Old Quarter. (Alone among that quartet, the Old Quarter still stands, albeit as a law office, at the corner of Austin and Congress.)

A collection of posters including a Liberty Hall poster featuring Bonnie Raitt and Little Feat, 1973

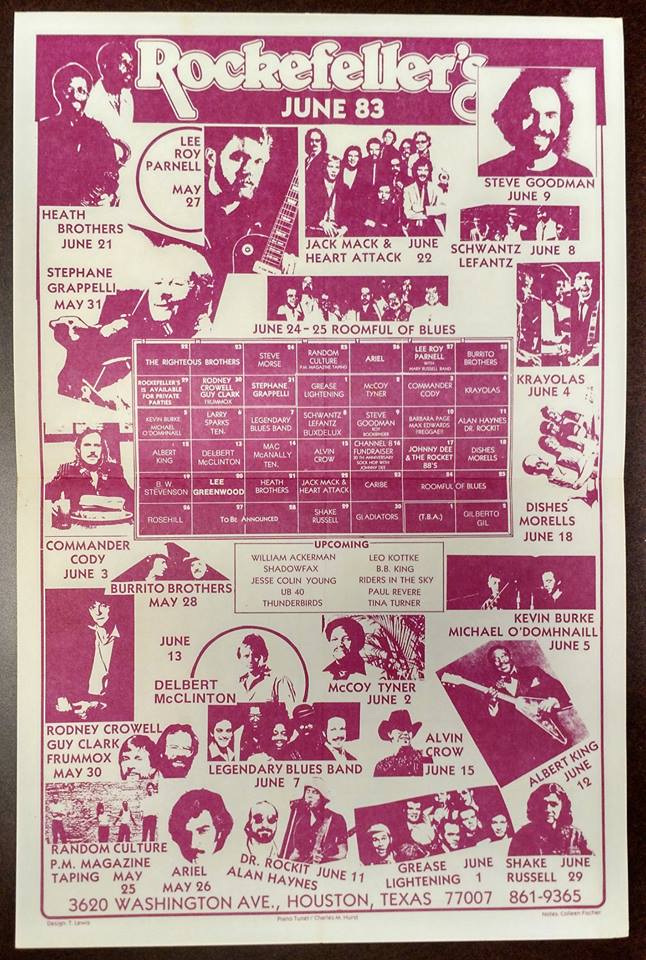

Rockefeller’s calendar mailer, June 1983. Rockefeller’s business records, 1978-2016

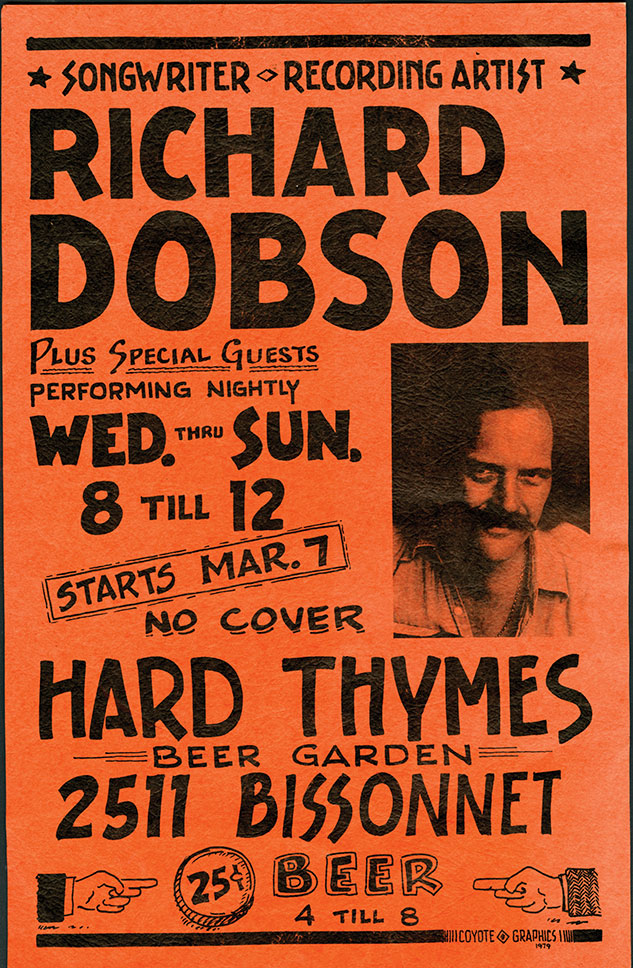

Richard Dobson concert poster from Hard Thymes

Lynn Langham from the “Through the Dark Nightly” LP cover, 1976

Don Sanders at Anderson Fair Retail Restaurant, photographer Bob Riegel, ca. 1976

Anderson Fair Retail Restaurant is the sole survivor among the venues from the Houston folk heyday, and Guthrie makes the most of its continued existence. She tends bar at the listening room in deepest Montrose and handles their social media. Serendipitous meetings with folk scene veterans tend to follow such real-world involvement, as do musical donations. Once the donations are in hand, Guthrie tries to process them and make them available as quickly as possible. “I immediately try to promote it,” she said. “I just want people to be able to look at me and say ‘Oooh, she’s active.’”

As an unintended consequence, the archive binds its donors to Rice, and in a single week last fall, two luminaries of the Houston folk golden age spoke in classes: Houston-bred, Austin-based troubadour Vince Bell discussed his agonizing six-year recovery from a devastating traumatic brain injury he suffered in a 1982 car wreck, while Richard Dobson discussed the Houston folk scene as a musical subculture. I caught up with both of them on campus, and their statements bore out something Guthrie had told me earlier: Posterity is very much on the minds of Houston folk legends, many of whom are now in their 70s.

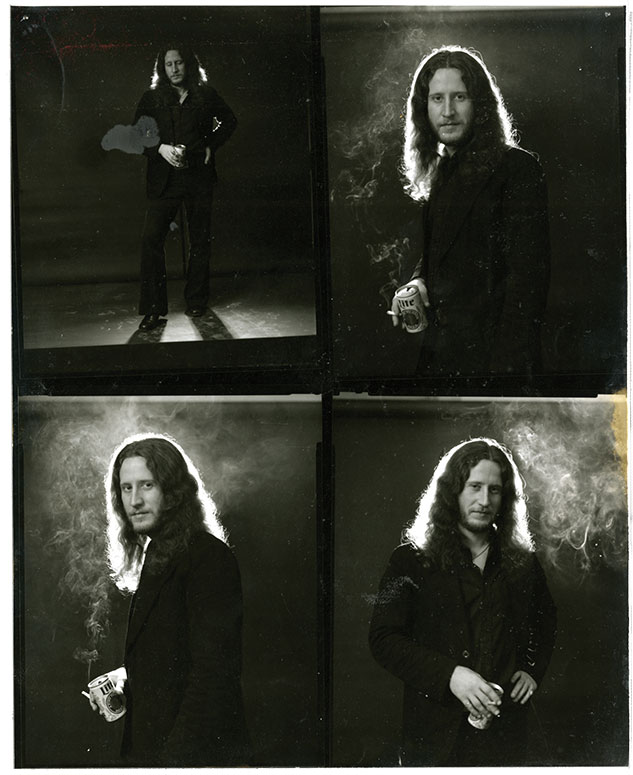

Vince Bell photo shoot, ca. 1976

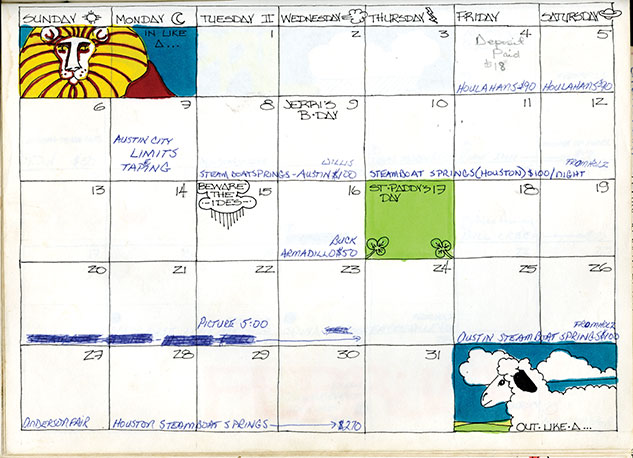

Calendar drawn by Jean King from Vince Bell’s journal, 1976

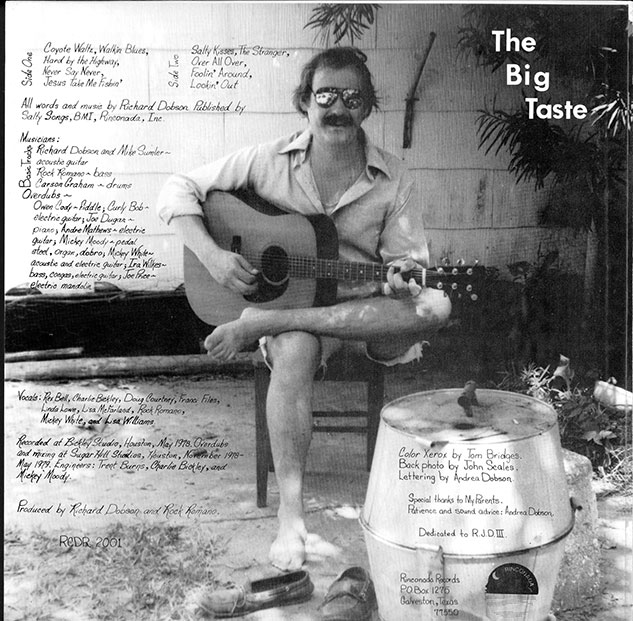

“It makes me feel great. If not immortality, it’s at least knowing that your stuff is gonna be there,” said Dobson, a former bandmate of Van Zandt’s, who co-wrote Clark’s “Old Friends” and has 23 albums under his own name. Last spring, Dobson, who lives in Switzerland, donated several boxes of correspondence, business files, journals and recordings to the archive.

Back cover of Richard Dobson’s LP “The Big Taste”

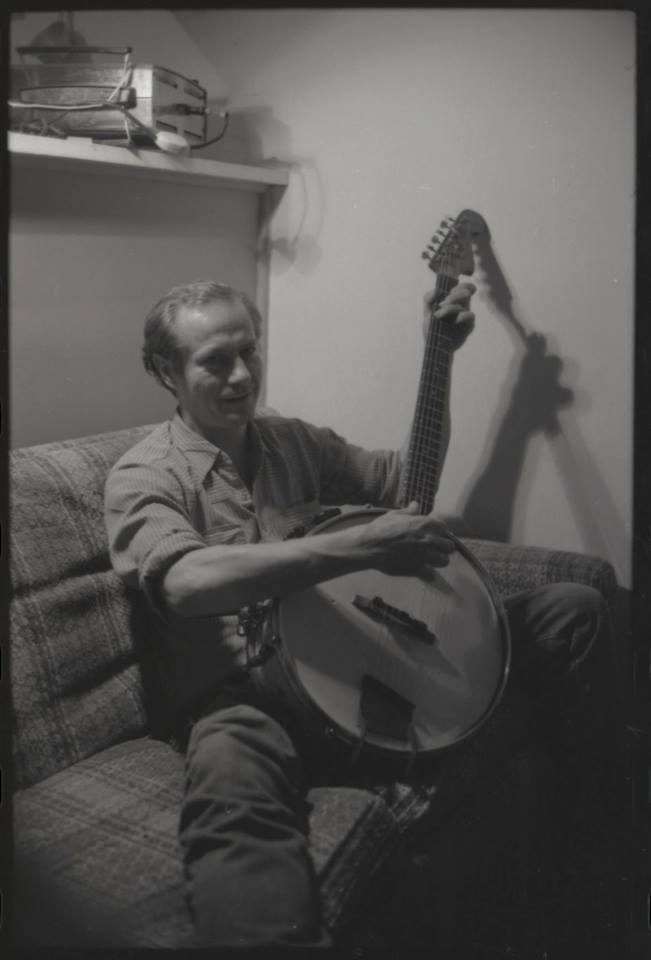

Frank Davis playing his invention the daddy banjo, photographer Joseph Lomax. Courtesy of John Lomax III

“It’s almost like I am looking at my life in retrospect, and that’s a little scary. So it’s a little sobering in that respect, but I’m really grateful that Norie is putting this together.”

Bell said that knowing his work would one day end up in the permanent collection of a school like Rice would have meant the world to him when he first strummed a guitar in earnest 46 years ago. “This is what an author covets, cherishes: recognition,” he said. “And everything I do from here on out goes into the archive, so I have inspiration to go further.”

Dobson is sending still more of his material over from his home on the banks of the Swiss Rhine, so much of it that it will necessitate shipping via the Port of Houston. To Dobson, it’s worth it. “Who’s gonna see it in Europe?” he said. “… I’ve already written two memoirs, and I don’t think I’m gonna be writing any more memoirs or autobiographies.”

There is always room for more material in the archive, Guthrie said. Her wish list includes the papers and memorabilia from people like K.T. Oslin, who, before her mainstream country success in Nashville, sang folk in Houston as Kay Oslin; Nanci Griffith, who immortalized Anderson Fair in the song “Spin on a Red Brick Floor”; Eric Taylor, Griffith’s former husband and a musical mentor to Lyle Lovett; and Lovett himself. Additional funding would be an enormous help in digitizing VHS tapes and other outdated media (and securing the server space to store them). Guthrie shares her archival discoveries on this and other projects via her blog, “What’s in Woodson.”

Discovering this obscure scene was as much an eye-opener to Guthrie as this archive will be to visiting scholars and fans. “I wasn’t necessarily a fan of this kind of music when I first started,” she said. “I wasn’t against it, either. ‘Pancho and Lefty’ was one of my favorite songs growing up, but I never knew it was written by Townes Van Zandt.”

Excavating further, she’s discovered treasure upon treasure deep in the Houston clay. “I didn’t know that all this music came from here, and I have become a fan,” she said. “As an archivist, I just want to preserve things. I feel like something special happened here that needs to be saved before it’s lost.”